In the quiet, unassuming region surrounding the Belgian city of Mons, a wave of terror gripped the community between 1996 and 1997. It wasn’t the terror of a shadowy figure lurking in the night, but something perhaps even more unsettling: the methodical and macabre dismemberment of women, their body parts scattered across the landscape in a bizarre and disturbing puzzle. The perpetrator, dubbed “The Butcher of Mons” by the media, left behind a legacy of fear and unanswered questions, a chilling testament to the darkness that can lurk beneath the surface of seemingly ordinary places.

The victims of the Butcher of Mons shared a tragic common thread: they were all women, often marginalized or vulnerable, who frequented the area around the Mons railway station. Their lives, already precarious, were brutally cut short, their bodies subjected to a chilling level of mutilation. The systematic dismemberment, a key characteristic of this case, suggests a killer operating with a disturbing degree of precision and control.

The first jarring discovery occurred in January 1996. The pelvis of Carmelina Russo, a 42-year-old woman who had disappeared earlier that month, was found in the Scheldt River, across the border in France. This initial finding, though horrifying, was just the beginning of a grim series of discoveries that would plague the region for over a year.

The following months brought further unsettling finds. In July 1996, the torso of Martine Bohn, a 43-year-old former prostitute from France, was pulled from the Haine River near Mons. The systematic removal of the head and limbs was a chilling hallmark of the killer’s methods, making identification difficult and adding to the overall sense of horror.

The year 1997 brought even more gruesome discoveries. In March, police officer Olivier Motte made a disturbing find: nine garbage bags containing human remains beneath the Rue Emile Vandervelde in Cuesmes. These bags contained the arms and legs of three different women, including those of 33-year-old Jacqueline Leclercq, a mother of four who had gone missing in December 1996. The sheer number of body parts and the calculated way they were disposed of painted a picture of a killer who was not only brutal but also meticulous.

Further discoveries in March and April of 1997 revealed more pieces of the puzzle. A tenth bag, containing a woman’s torso, was found on the Chemin de l’Inquiétude (Path of Worry), a chillingly named location. Two bags found near the Haine River contained a foot, a leg, and a head. The locations where the remains were found, often with evocative names like “Avenue des Bassins” (referring to the pelvis) and “Chemin de Bethléem” (Bethlehem) near the river Trouille (French for “fear”), added a bizarre and unsettling layer to the case.

The final victim identified in this horrifying spree was Begonia Valencia, a 37-year-old woman who disappeared from her home in Frameries in the summer of 1997. Her skull was later found in Hyon. The discovery of her remains marked the end of the known killings attributed to the Butcher of Mons, but the mystery of who was responsible remained unsolved.

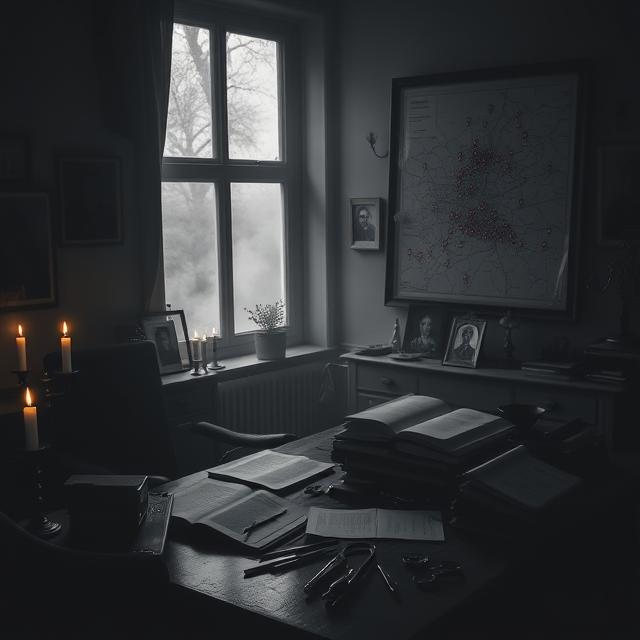

The investigation into the Butcher of Mons murders was complex and challenging. The systematic mutilation of the bodies made identification incredibly difficult, hindering the ability to piece together the victims’ lives and potentially find clues to the killer’s identity. The initial investigation was hampered by a lack of resources, as the case was initially considered “local” and did not receive the attention it ultimately warranted. A special investigation cell, called the Corpus cell, was eventually formed, led by magistrate Pierre Pilette, but the killer had already vanished.

Despite the challenges, investigators pursued several leads and considered numerous suspects. One name that emerged was Smail Tulja, a Montenegrin man who was later convicted in Montenegro for the 1990 murder of his wife in New York City. Tulja had fled to Belgium after his wife’s murder and was suspected of being the Butcher of Mons. The fact that the victims in both cases were dismembered and found in garbage bags added to the suspicion. Tulja was also a suspect in two murders in Albania. However, despite the circumstantial evidence, no concrete link was ever established between Tulja and the Butcher of Mons murders. He died in prison in 2012, taking any potential answers with him.

The lack of a definitive suspect and the passage of time have left the Butcher of Mons murders unsolved. The case remains a chilling reminder of the dark side of human nature and the frustrating reality of unsolved crimes. The victims, whose lives were brutally taken, deserve to be remembered, and the mystery of their killer continues to haunt the region.

The Butcher of Mons case stands out not only for its brutality but also for the bizarre nature of the body disposal. The scattered remains, the calculated dismemberment, and the often-evocative locations where the body parts were found all contribute to a sense of unease and a lingering question: what drove this killer to commit such horrific acts?

The case also highlights the vulnerabilities of marginalized individuals. The victims, often women who frequented the Mons railway station and faced socio-economic challenges, were perhaps easier targets for a predator. Their disappearances might not have been noticed as quickly, and their cases might not have received the same level of attention as those of more privileged members of society.

The legacy of the Butcher of Mons is one of fear, frustration, and unanswered questions. The case serves as a cautionary tale, a reminder that even in seemingly peaceful communities, darkness can lurk beneath the surface. The victims of the Butcher of Mons deserve to be remembered, and the search for answers, however unlikely, should never be completely abandoned. The chilling puzzle of the Butcher of Mons remains, a grim chapter in the sinister archive of true crime.

Want to explore the shadows even deeper? For more chilling cases like this, visit SinisterArchive.com, where the legends are real.