The cobbled streets of late Victorian London, already steeped in a miasma of coal smoke, poverty, and the lurking dread of the unknown, were further darkened by a series of gruesome discoveries that sent a chill deeper than the Thames’ icy currents. While the specter of Jack the Ripper, who would later terrorize Whitechapel, looms large in the popular imagination, a decade prior, between 1887 and 1889, a different kind of horror unfolded along the banks of the River Thames and within the city’s shadowy recesses: the Thames Torso Murders. These killings, characterized by the systematic dismemberment of at least four women, paint a macabre picture of a killer operating with a chilling efficiency, a phantom whose legacy, though less sensationalized than the Ripper’s, remains a haunting testament to the era’s pervasive violence and unsolved mysteries.

To truly understand the terror these murders instilled, one must first immerse oneself in the atmosphere of London during this period. The late 19th century was a time of stark contrasts – burgeoning industrial progress juxtaposed with deep-seated poverty, opulent wealth existing alongside unimaginable squalor. The River Thames, the city’s lifeblood, was also a repository of its secrets, its murky depths often concealing the unwanted and the tragic. It is within this grim backdrop that the story of the Torso Killer unfolds.

The first jarring note in this sinister symphony struck in 1887. On June 5th, near Rainham, a headless and limbless torso of a woman was dredged from the Thames. The discovery sent ripples of unease through the city, a disquiet that would soon escalate into outright fear. This initial finding was not an isolated incident. Over the next two years, similar remains – torsos without heads or limbs – would surface in various locations along the river and within the urban sprawl itself.

The victims, much like those who would later fall prey to Jack the Ripper, were believed to be women of the night, the marginalized souls who navigated the perilous underbelly of Victorian society. Their precarious existence made them vulnerable, their disappearances often unnoticed or deemed insignificant by the wider populace and, at times, even the authorities. This societal indifference, though lamentable, was a grim reality of the era.

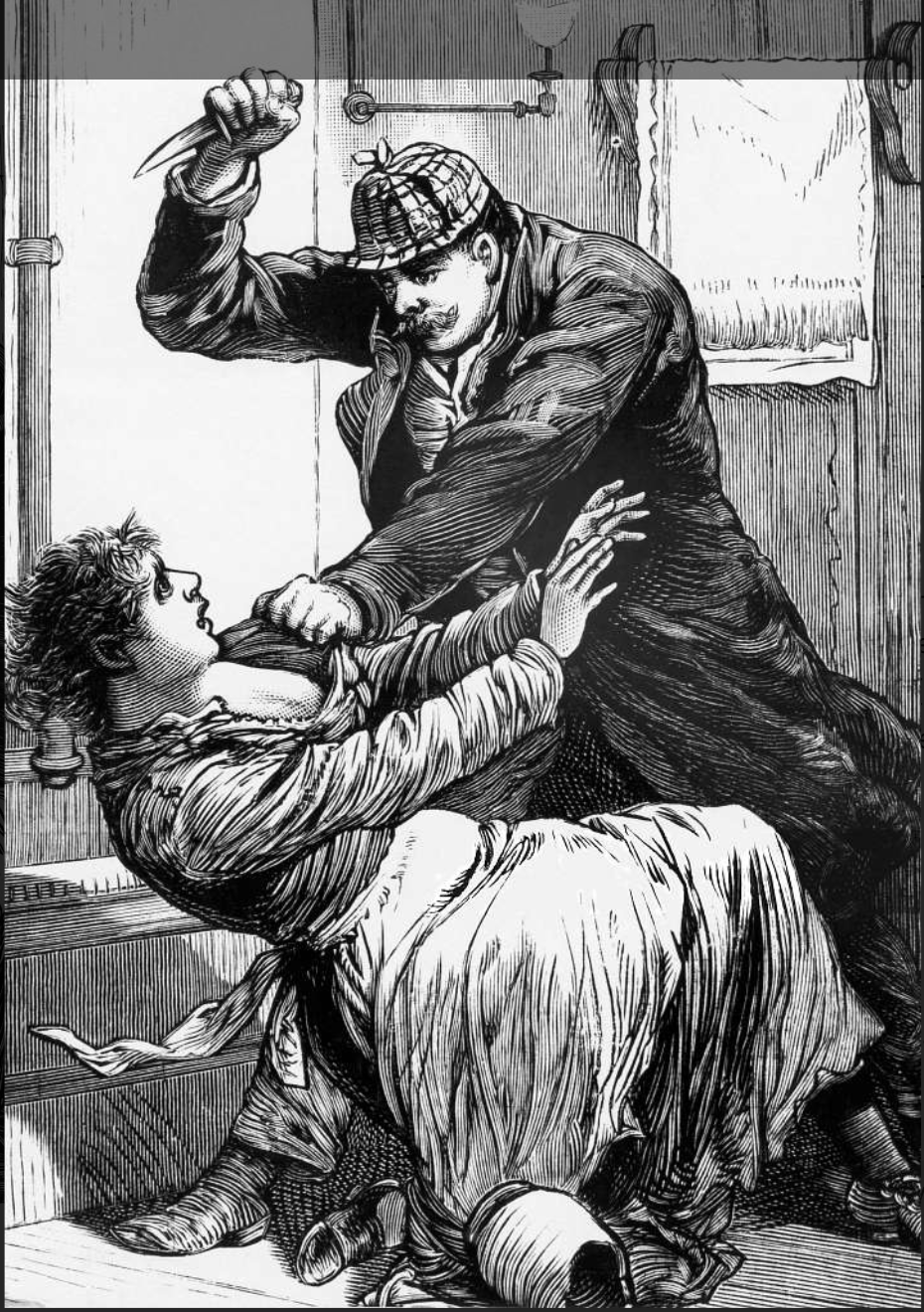

One of the most unsettling aspects of the Torso Murders was the methodical nature of the dismemberment. Unlike the Ripper’s more localized and arguably frenzied attacks on the abdomen and throat, the Torso Killer seemed focused on the complete removal of identifying features – the head and the limbs. This suggested a deliberate attempt to not only dispose of the bodies but also to obliterate any immediate means of identification. The precision, or at least the consistency, of this dismemberment hinted at a grim purposefulness.

The investigation into these horrific crimes was fraught with challenges. The lack of heads and limbs rendered traditional methods of identification, such as facial recognition or fingerprinting (which was still in its nascent stages), utterly useless. The victims remained largely anonymous, their stories silenced by the killer’s brutal actions and the societal indifference towards their plight.

The press of the time, while perhaps not as fixated as they would later be with the Ripper, did report on the discoveries, and the specter of a “Torso Killer” did briefly haunt the public consciousness. However, the lack of sensational details, such as the Ripper’s taunting letters or the specific nature of his mutilations, perhaps contributed to the Torso Murders eventually fading somewhat from the public’s immediate memory. Yet, for those tasked with investigating these crimes, the horror was undoubtedly palpable.

Several discoveries punctuated this grim period:

- June 1887 (Rainham): The initial headless and limbless torso found in the Thames.

- September 1888 (Whitechapel): The torso of a woman was found in Buck’s Row, the same location where Mary Ann Nichols, the Ripper’s first canonical victim, was discovered just weeks prior. This discovery inevitably led to speculation about a possible link between the two killers.

- October 1888 (Pinchin Street): Another headless and limbless torso was found, further fueling the fear that a second, equally brutal killer was at large.

- June 1889 (Whitechapel): The final torso linked to this series was discovered in the Thames near Shadwell.

These discoveries, clustered around the time of the Ripper’s most intense activity, naturally led to theories connecting the two series of murders. Could the Torso Killer and Jack the Ripper have been the same person? Or were two distinct, equally monstrous individuals preying on the vulnerable women of London?

The prevailing view among many contemporary and modern-day researchers is that the Torso Killer and Jack the Ripper were likely separate individuals. The methods of mutilation differed significantly. The Ripper focused on abdominal and throat wounds, often leaving the limbs intact, while the Torso Killer’s hallmark was the removal of heads and limbs. Furthermore, the geographical focus differed somewhat, although there was overlap in Whitechapel.

Despite the lack of a definitive link to the Ripper, the Torso Murders stand alone as a series of horrifying and unsolved crimes. The identity of the killer, their motives, and even the precise number of victims remain shrouded in the mists of time. Several individuals were considered as potential suspects, but none were ever conclusively linked to the crimes.

One notable figure often discussed in connection with both the Torso Murders and the Ripper killings is Francis Tumblety, an American quack doctor with a known misogynistic streak. He was in London during both periods of intense killings and was known to collect anatomical specimens. However, the evidence against him remained circumstantial.

Another suspect sometimes mentioned is George Chapman (born Seweryn Kłosowski), who was later convicted and executed for poisoning three of his wives. He was also present in London during the time of the Torso Murders, and his methodical use of poison bears a chilling similarity to the calculated dismemberment of the Torso Killer. However, direct evidence linking him to these earlier crimes is lacking.

The lack of forensic science as we know it today severely hampered the investigations. DNA analysis, advanced fingerprinting techniques, and detailed crime scene reconstruction were simply not available. Investigators relied heavily on eyewitness accounts (which were often unreliable), rudimentary physical evidence, and the nascent field of criminal profiling.

The social context of the time also played a role in how these murders were perceived and investigated. The widespread poverty and the large number of transient individuals in London made it easier for people to disappear without notice. The societal stigma surrounding prostitution also meant that the deaths of these women often did not elicit the same level of public outcry or investigative urgency as the murders of more “respectable” members of society.

Yet, the horror of the Torso Murders cannot be understated. The image of dismembered bodies surfacing from the Thames or being discovered in dark alleyways is deeply unsettling. It speaks to a level of brutality and dehumanization that chills the blood. These were not just deaths; they were acts of profound violence and a stark indictment of the dark underbelly of Victorian London.

The legacy of the Thames Torso Murders is one of a forgotten horror. Overshadowed by the more sensationalized Ripper killings, the victims of the Torso Killer have largely faded from public memory. Their stories, already obscured by their marginalized status in life, were further silenced by the brutality of their deaths and the failure of the investigations to bring their killer to justice.

However, within the archives of true crime, the Thames Torso Murders remain a potent reminder of the darkness that can lurk in the shadows of even the most advanced societies. They serve as a historical counterpoint to the Ripper narrative, illustrating that the late Victorian era was plagued by more than one monstrous predator.

The enduring mystery of the Torso Killer invites us to consider several unsettling questions: What motivated these gruesome acts? Was it a deep-seated misogyny, a pathological need to mutilate, or something else entirely? Could the killer have been someone who moved seamlessly through the city’s underbelly, unnoticed until their horrific acts came to light? And why have these murders been so comparatively forgotten in the annals of crime history?

Perhaps the lack of a catchy moniker like “Jack the Ripper” contributed to the fading of the Torso Killer from public consciousness. Or maybe the nature of the dismemberment, while equally horrific, lacked the specific kind of terror that the Ripper’s more visceral attacks evoked. Whatever the reason, the victims of the Thames Torso Murders deserve to be remembered, and their tragic fates should not be relegated to the dusty corners of historical crime.

In revisiting these forgotten crimes, we not only pay respect to the lives lost but also gain a fuller, albeit darker, understanding of the complexities and dangers of Victorian London. The shadow of the Thames Torso Killer lingers, a chilling testament to the unsolved horrors that once haunted the great metropolis. The legends, indeed, are real, even those less frequently whispered. The Thames, that silent witness, still holds the secrets of its forgotten dead.

Want to explore the shadows even deeper?

For more chilling cases like this, visit SinisterArchive.com—where the legends are real.